The pandemic’s effect on women in ForumCiv’s program countries

UN Women Executive Director Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka summed up much of the essence when she said:

“It’s clear that the COVID-19 pandemic is hitting women hard - as victims of domestic violence locked down with their abusers, as unpaid caregivers in families and communities, and as workers in jobs that lack social protection.”

Cambodia has managed to keep infection levels low but the economic hardship that follows the shutdown of business and schools is affecting hundreds of thousands of especially female workers. Mass unemployment is currently underway and the World Bank estimates that 1.76 million jobs could be lost. A possible EBA trade withdrawal could further add to the unemployment rate. The garment industry is the country’s biggest employer, where women constitute 80 per cent of workers. Women are often recruited from rural areas and have families that rely on the remittances they send back.

Loss of income typically translates into debt. Cambodia ranks as the highest average amount to micro-financing loans in the world, but unlike other big micro-financing countries, the lenders are private and for-profit. Women’s rising unemployment and the subsequent debt crisis may have devastating effects on poverty according to Ian Ramage, director of Angkor Research.

“Cambodia has been on a good run and has some economic resilience. But if this trend continues, Cambodia is at risk of reversing 20 years of development and going back to being a country with a 40 per cent poverty rate.”

Kenya struggled with high rates of teenage pregnancies before COVID-19 and the pandemic have not eased the situation. When schools go into lockdown, girls are left with busy parents and out of the eyesight of teachers who can sound the alarm in suspected abuse cases. Restrictions on movement make contraceptives harder to come by and curfews increase the danger of sexual abuse.

Teenage pregnancy is a complex issue to apply clear cut statistic on and it is too soon after lockdown and curfew restrictions to draw any certain conclusions. But anecdotal and regional surveys suggest a Corona effect on the matter. Elizabeth Mariara is a nurse running a reproductive health clinic in rural Kenya. This year she has had 30 teenage pregnancy cases between April and June, that figure was four for the same period in 2018 and three in 2019. While media reports that the county of Machakos alone have had 4,000 adolescent girls requesting gynaecological services.

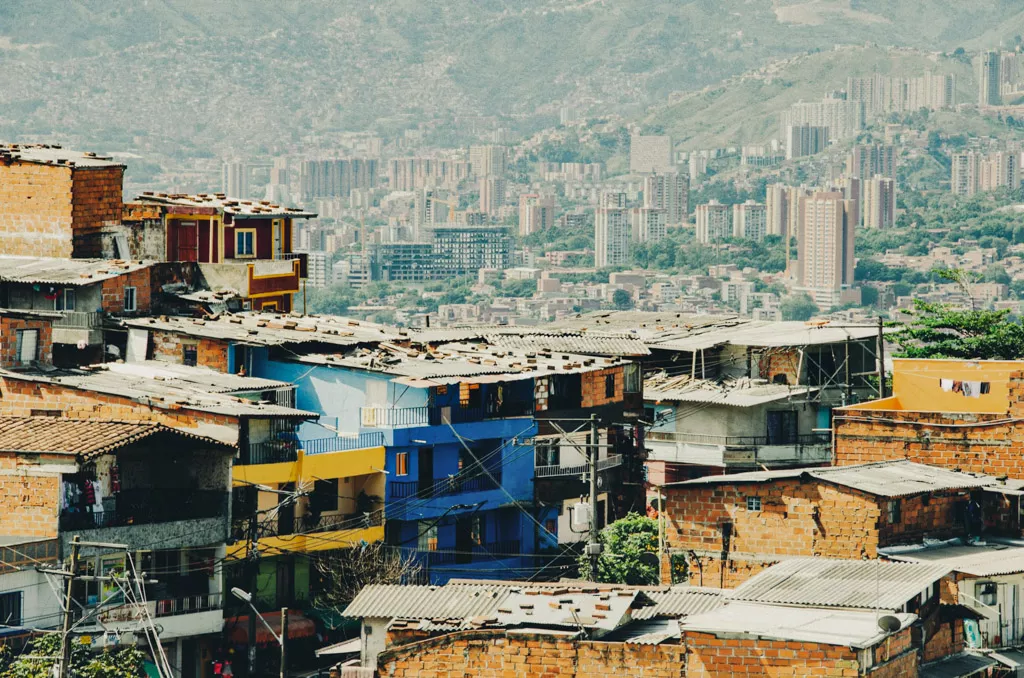

Colombia has seen one of the highest counted cases of COVID-19 in the world. Similarly, since curfews were introduced cases of violence in the home have skyrocketed. Data suggests a 175 per cent increase in reported cases of domestic violence. During more ordinary times domestic violence is one of the most underreported types of crimes and the pandemic is likely to hide even larger numbers than normal. Carlos Fernando Galván Becerra works at Organización Feminina Popular and he explains why.

If a woman lives with her abuser and she has to return to the home after reporting him, there is the risk that he might become even more violent if he finds out.

“Lockdown makes it more difficult to leave the house. And while women can theoretically report domestic violence online or by calling a special number, this is not always possible. Many homes in Colombia don’t have internet access. And it isn’t easy to make a phone call reporting abuse if you live under the same roof with your abuser. Moreover, if a woman lives with her abuser and she has to return to the home after reporting him, there is the risk that he might become even more violent if he finds out.”

Sweden did not enforce a legal lockdown but the decrease in people’s movement reflects that of countries with full lockdowns. Similar to Colombia, Sweden counts high levels of domestic violence as a consequence of COVID-19. Looking at reported cases of domestic violence from March to April, compared to the same months in 2019, there is an increase of 52 per cent. The negative effects on children are also evident as calls for help to children’s helpline Bris has increased with 30 per cent.

“We know that circumstances of social isolation, high stress and conflict levels, economic hardship and other challenges increase the risk of children experiencing violence in the home. We find ourselves in a societal crisis which offers all these ingredients while at the same time, the important safety factor of adults outside the family is less available.” Says social worker Marie Angsell at Bris.

Liberia, a country with all too much experience of fighting deadly viruses had a short breather between Ebola and COVID-19. One lesson learnt from the Ebola health response was that community engagement was solely focused on male gatekeepers and male community leaders. Meanwhile, women play a disproportional role in the disease response, carrying out services as nurses, field and voluntary staff. The social expectations of women taking responsibility for sick children and relatives are also by no means eased in a pandemic. In short, health care – formal or informal– rest on women’s shoulders.

The skewed balance between labour input and power is pointed out by Savior Mendin, Last Mile Health’s Country Manager for Grand Bassa Liberia. She notes that although women comprise 70 per cent of health workers globally, they only hold 25 per cent of leadership positions. In Liberia, the figure of men in decision-making roles often accounts to more than 90 per cent. This, she means, robs women and societies of the opportunity of innovative, cost-effective, and context-appropriate policies and interventions.

Ignoring the existence of COVID-19 and the women who shouldered its burden proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back.

In Belarus, the relaxed approach to the pandemic culminated in unprecedented protests against the sitting regime and President Lukashenko. ForumCiv’s Regional Manager for Eastern Europe, Ognjen Radonjic, describes the President’s recipe of ‘vodka, sauna and tractors’ as COVID-19 treatment as the breaking point for the social contract between the state and people. While the President was making fun of the “virus hysteria”, the health system was overwhelmed and people started crowdfunding for medical supplies.

Irina Solomatina, Head of Council of Belarusian Organization of Working Women, explains how 85,6 per cent of health workers are women. Yet, when counting women appearing in media on the Day of Global Media Reporting zero women in medicine could be seen on the four Belarusian news channels. Unlike many other countries, images of essential female workers on the pandemic frontline was nowhere to be seen in Belarus.

Ignoring the existence of COVID-19 and the women who shouldered its burden proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back. The President, who during his election campaign claimed that women can not be leaders because “poor thing is so fragile, so weak that she would collapse under the burden of responsibilities” soon came to see three women organising an oppositional campaign. The feminist movement changed the course of the oppositional protest to peaceful civic movement.

The global citizenry will have to live with the social, psychological and economic effects of this pandemic for many years to come. If we wish to ease the journey ahead of us, it would be wise to consider the experiences of those hardest hit. To begin with, that would require a gender lens on any COVID-19 response analysis done. Something that today is only done by 20 per cent of countries of the world and done very well by only 12 per cent.

Other recent articles

Aremos Paz: ploughing furrows of peace in Colombia

After five years the Aremos Paz project have come to an end. Read more about how the project have supported rural communities and the reincorporated population in rural areas affected by the conflict...

12 times civil society changed the world in 2023

Strengthening press freedom, dismantling structural discrimination, eradicating harmful practices, maintaining a helpline despite state crackdown, preserving natural resources, these are just some of...

Inspiring inclusion: International Women’s Day 2024 celebrations

“It's crucial for us to create a world where women are empowered to take leadership roles in their communities and beyond."