Better to be a Maasai cow than a Maasai woman: A tale of two Maasai men

At the crack of dawn, as the first golden rays of sunlight kiss the savannah, Ole Kantai rises from his bed. It’s 6 a.m.—a sacred hour for any pastoralist. He makes his way to the cowshed, guided by instinct and generations of tradition. He begins his headcount: one cow after another, until he reaches 300. Each one accounted for. Each one is a symbol of status, pride, and legacy. Satisfied with their health, he turns back toward his home.

On the path, he meets Noonkishu, his wife, heading out with a calabash in hand to begin the morning milking. He greets her briefly, then asks, almost as an afterthought, “How are the children?”

Noonkishu sighs. “They are well… but two boys have a bad cough, maybe pneumonia. And three others—one boy and two girls—have been sent home from school. School fees.”

Ole Kantai frowns, shakes his head, and tells her to finish milking and take the sick children to the hospital. But Noonkishu hesitates. She had planned to go to the market to sell vegetables to contribute to her merry-go-round savings group. Could the hospital wait until tomorrow?

“No,” Kantai snaps. “Today. The hospital comes first.”

Then, as if granting a rare gift, he mentions that he received money from the milk cooperative. It will be enough to return the boy to school. As for the two girls? “We’ll wait for the government bursary,” he says dismissively.

Noonkishu dares to propose a different idea— “What if we sell one cow? Just one, so all three can return to school?”

The air stills.

Kantai’s face hardens. “Are you mad?” he growls. “You speak like a fool. You think cows grow on trees?”

In Maasai culture, a cow is not just livestock. It is sacred. It is wealth. It is status. It is life.

A single cow fetches about KSh 60,000 in the current market. With 300 cows in his herd, Ole Kantai is worth KSh 18 million. And yet, he would rather let his daughters remain at home—their futures in limbo—than sell even one.

Why? Because in this culture, a cow holds more value than a woman. In fact, to some, it is better to be a Maasai cow than a Maasai girl.

Before a girl can even finish school, she’s often married off—in exchange for cows. A marriage contract inked in livestock, not love. Education, dreams, autonomy—sacrificed on the altar of tradition.

From Ole Kantai’s story, we see more than just poverty. We witness the erasure of the woman’s voice, the denial of agency, and layers of emotional and financial abuse. Women are confined to household chores, barred from decision-making, and excluded from property ownership. Even when they try to help, they’re silenced.

But not all stories end in silence.

Enter Ole Sunkuyia—another Maasai man, but of a different kind. A man who sees things differently.

He stands tall, introducing his daughter, Namunyak (meaning "the lucky one"), with pride. She has just completed university with a degree in education and has received her employment letter from the Teachers Service Commission (TSC).

“She will return the cows we sold for her education,” he smiles. “And she will support her family, not depend on any man.”

His wife, too, he says, has been a pillar—contributing to household expenses and easing the mental burden he once carried alone.

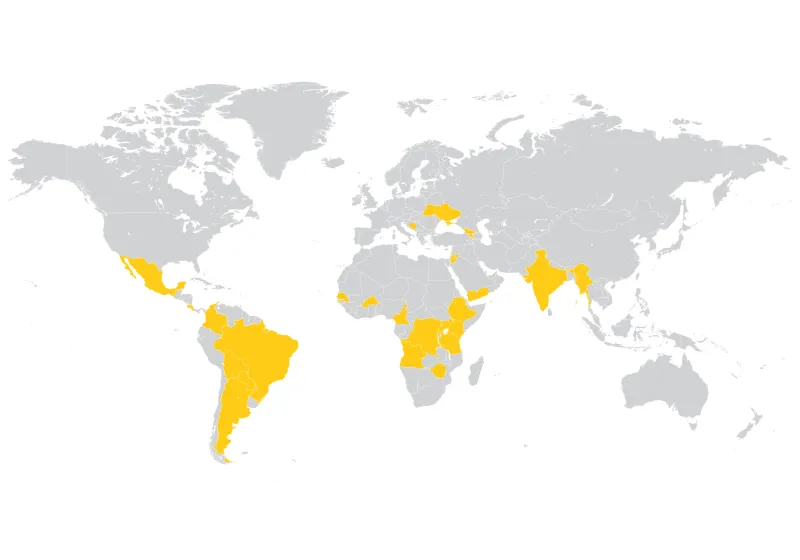

Ole Sunkuyia is now a champion for women’s and girls’ rights, particularly in education and sexual and reproductive health. He inspires young men in his community to break free from harmful traditions and see the potential in their wives and daughters.

Thanks to grassroots empowerment programmes, many are beginning to listen. Some men are now selling cows to send girls to school, allowing women to engage in productive work, and granting them autonomy over their bodies and futures.

But change is slow.

And the bitter truth remains: “A Maasai man loves his cows more than his six wives.”

That is not satire.

It is a confession. A tragedy. A mirror.

A cow dies, and men wail.

A woman suffers, and they say, “She is strong.”

This story is not just about cattle. It’s about culture, contradiction, and courage. It forces us to ask:

How can a community that reveres cows so deeply fail to recognize the worth of the ones who give life, nurture children, and carry generations within their bodies?

The Maasai cow is sacred. But the Maasai woman is the soul. It’s time we honored both.

This article is co-authored by Mercy Koini, ForumCiv Programme Officer- Gender Equity and Social Inclusion and Parsanka Sayianka, a gender equality champion.

Other recent articles

The power of people powered Public-Private Partnerships

Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) are often discussed in terms of roads, power plants, housing, and other large infrastructure projects. But as discussed on the People’s Partnership Podcast, PPPs are...

ForumCiv’s social media accounts labelled as “extremist materials” in Belarus

Important message to our Belarusian followers. Any interaction with our content can now lead to legal consequences in Belarus. Please read the information below and take the necessary precautions for...

ForumCiv enters new strategic partnership

ForumCiv is proud to announce a new three-year strategic partnership with Sida, totalling SEK 137 million.