Journalism without fear or favour: staying true to the cause

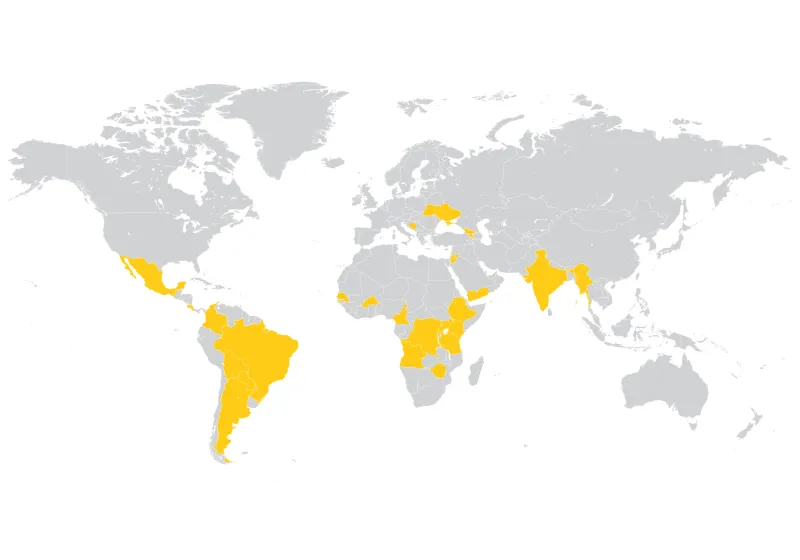

World Press Freedom Day (WPFD), commemorated globally on May 3, celebrates the fundamental principles of press freedom. Importantly, it is a day of support for the media, which is often a target for persecution, attacks, restraint or abolition by state and non-state actors.

The theme for the 2020 WPFD is Journalism Without Fear or Favour. This theme seeks to highlight issues around the safety of women and men journalists and media workers; advance independent and professional journalism free from political and commercial influence, and to promote gender equality in all aspects of the media.

This year’s commemoration comes at a time the world is grappling with the Covid-19 pandemic, which has disrupted many aspects of freedom of the press, with increased state control over information seen essential to combating the pandemic.

We sat down with John-Allan Namu, an award-winning investigative journalist and the CEO of Africa Uncensored, a Wajibu Wetu Programme partner using investigative journalism to deepen human rights and democracy.

As a well-seasoned journalist, what is your assessment of press freedom in East Africa today?

John-Allan: The past couple of years haven’t been very good for press freedom in East Africa perhaps except for Ethiopia, which has been experiencing some renaissance since the coming to power of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. The rest of East Africa has had a bad run regarding press freedom with a myriad of cases curtailing freedom of the press. The killing of journalist Peter Moi in South Sudan; the disappearance of Azory Gwanda in Tanzania. It’s now over 700 days since his disappearance, and we still don’t know where he is, we presume that he is dead. Look at Uganda when it comes to coverage of opposition rallies.

Overall if we are to compare with twenty years ago, we have taken some steps forward, but there’s still a long way to go in terms of achievement freedom of the press.

What are the most pressing issues today regarding freedom of the press in East Africa?

John-Allan: Access to information remains vital. Most African governments are starting to digitise crucial public information and coming to terms with the fact that information is a public right. It’s been a challenge for a lot of these governments to adapt to this. Some countries like Kenya have Access to Information Act, yet it remains a challenge to access the information that you need even if you follow the laid down protocols as guided by law. The situation is much harder for countries where they don’t even have these laws in place.

How can the media practitioners push back against infringement on freedom of the press?

John-Allan: Recently, Citizen TV Kenya was forced to apologise to Tanzanian President Magufuli for coverage of his handling of the Covid-19 in Tanzania. This moment should have been a critical marker for journalists and media organisations across the country to rally behind Citizen TV and say that, you do not have to not apologise for poking holes in a strategy that seems to be failing them. Being cowered by foreign governments in your country over coverage that seems fair and balanced is the last thing that we should want.

However, the silence that followed speaks to the broader collapsed sense of unity between journalists and media organisations. I think the criticism of the media has forced some introspection at some levels but also a defensiveness of some sorts, forcing journalists into their corners where they don’t feel empowered enough to stand together arm in arm. As media practitioners, we seem to be at odds at very crucial points.

We are not standing up and defending one another and defending the very hard-won rights. That’s the most important thing we could do to ensure that our rights are not eroded, are not abrogated and that we can even claim more space.

Acknowledging the difficulty of focusing on long-term consequences amid the Covid-19 pandemic, how do you see the long-term impact on the information systems and press freedom?

John-Allan: Covid-19 is a disrupter like none other. It’s disrupted our way of lives and harmed our economies in ways we are yet to understand. This pandemic is changing the way the world will work.

I am hopeful that Covid-19 will peel back the mask of control and iron-fisted rule and show what lies behind it, which is ineptitude in many cases. I hope the pandemic shakes us out of the sense that we have a government that we must listen to and abide by at all times, and if you don’t you end up being beaten by the police. In the end, it will force the governments and people in charge, to bargain, seek information from the public and the various expertise and admit that sometimes, they don’t have all the answers. That sense of consultation and communication then becomes a new way of dealing with the public and the press.

What can the media do to ensure the provision of accurate information at a time when truth and facts seem relative?

John-Allan: The media should recognise that giving public information is essential. Still, the obligation to provide the information quickly without having verified it is something that they should refrain from. What Covid-19 pandemic is showing us is that there is a lot of diverse experiences in various significant fields like the medical field, in managing disasters and even ideas on how to turn around economies in the current challenges.

The role of a journalist is to go out and seek these diverse sources of information, interrogate these sources, hold them up against what we are being told and verify that information. Look at Donald Trump's comment about ingesting or imbibing detergents, the first people to contradict him were the scientists, and this played out in the media. You can see how that’s helping saves lives literally and helping people make better decisions. That’s what journalists can do.

What about development actors, what can they do to enhance the freedom of the press?

John-Allan: Development actors can support media organisations and mainstream media and look at the civic space as something that media contributes to safeguarding alongside other actors like civil society, artists, medics amongst others. Looking at society as key protectors and beneficiaries of civic space and continue supporting initiatives that seek to do that.

One thing that Covid-19 pandemic is teaching us is that everybody is fighting challenges in their own backyards. Now is the time for local actors to come up with own solutions that are independent of foreign funding. Philanthropy becomes more of a local prerogative. If we don’t have the kind of local institutions that can support us through this time, then no one can come to build those institutions for us. Now would be a good time to be reflective about the gaps that development partners have been filling and look at how can we fill them. We need to build the institutions, protect the organisations that are working for public goods and do it ourselves!

How optimistic are you about the future of democracy with a specific focus on press freedom?

John-Allan: I am somewhat hopeful. A lot of people are starting to recognise the right to information, and acknowledging press freedom is a public good. I think a lot more people would be willing to stand up and support people who are fighting to secure those rights.

Other recent articles

The power of people powered Public-Private Partnerships

Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) are often discussed in terms of roads, power plants, housing, and other large infrastructure projects. But as discussed on the People’s Partnership Podcast, PPPs are...

ForumCiv’s social media accounts labelled as “extremist materials” in Belarus

Important message to our Belarusian followers. Any interaction with our content can now lead to legal consequences in Belarus. Please read the information below and take the necessary precautions for...

ForumCiv enters new strategic partnership

ForumCiv is proud to announce a new three-year strategic partnership with Sida, totalling SEK 137 million.