Colombia's other (historical) virus

The current Covid-19 pandemic has affected Colombia as much as the other countries in the region, despite a long lockdown (one of the longest in the world, since mid-March) and early measures taken by the national and local authorities.

According to official data, Colombia is at the top of the list of countries in number of cases per million people

(Source: Our World in Data, last updated August 25th).

But there is another vicious threat, spreading on many regions in the country, an unhealthy situation that has reawakened and blurred the hope for peace in many communities.

Unfortunately, social and political violence, a phenomena that has been enrooted in the core of Colombian history for more than a century and which was valorously chased away with the Peace Agreement efforts between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrilla (in 2016), has returned with its uglier face, already known to many in the country.

Unfortunately, social and political violence has returned with its uglier face, already known to many in the country.

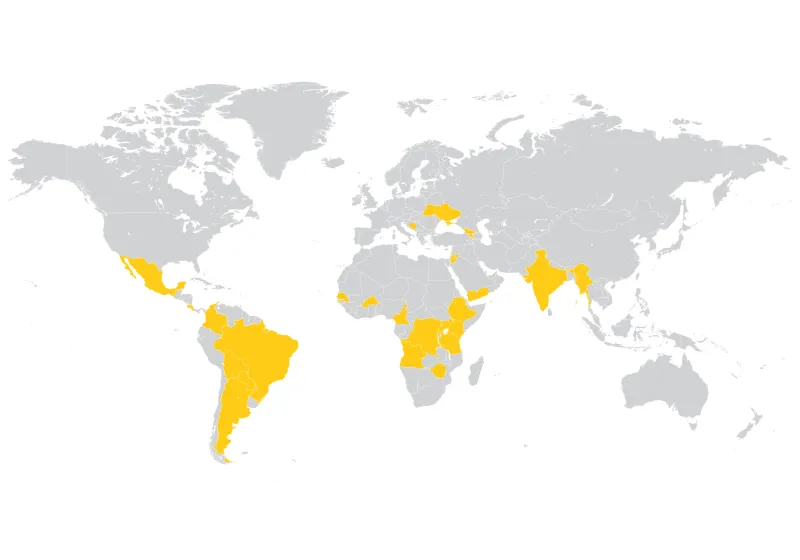

After over 50 years of internal conflict, Colombia has remained the deadliest country for human rights defenders in 2019, according to Front Line Defenders and more recently to Michel Forst, the former UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders. Colombia is the country with the most internally displaced people, and the second most unequal country in Latin America, according to UNHCR and the World Bank. And sadly to say, things are not getting better.

Human rights defenders, “easier” targets during COVID-19

Already at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, high-profile leaders were targeted by illegal groups. During the quarantine, as we already reported earlier in the year, a plan was exposed to kill Jani Silva, a human rights defender advocating for peace and the environment in the Putumayo region, a community leader of ADISPA (Association for the Integral and Sustainable Development of the Amazon Pearl), a ForumCiv partner organisation in the Colombia country programme projects.

Many other defenders around the country have received death threats with illegal groups moving around freely, even in territories with a high number of military bases, such as the Cauca region, in south eastern Colombia. The country's quarantine restrictions have not decreased the killings of human rights defenders and instead made them easier targets. In many cases, they are murdered in their own homes, making staying home in the quarantine a dangerous risk. According to the Colombian NGO Institute of Development and Peace Studies (Indepaz its acronym in Spanish), more than one thousand human rights defenders have been killed since 2016, when the Peace Agreement was signed; in 2020 194 human rights defenders have been killed (that is, 4 victims every 5 days), as well as 41 Peace Agreement signatories (Farc ex-combatants).

Illegal armed groups are using restrictions on movement to gain territorial control during the pandemic. According to Human Rights Watch, illegal groups have imposed their own Covid-19 rules with curfews, lockdowns, and movement restrictions in at least 11 of the 32 Colombians provinces.

Massacres: the virus rears its ugliest head yet

In the midst of the pandemic, illegal armed groups of all stripes (Farc dissidents, paramilitaries, criminal organisations -mainly dedicated to drug trafficking and illegal mining, and guerrilla groups) have resorted to killing civilians to intimidate and to send the message to the population, at gunpoint, that they want to control their territories. Six massacres have been committed in the first 20 days of August, with 24 victims; among them 6 minors, three indigenous people and seven young people under 24. More than 180 people have been killed in massacres during 2020, and as this story is being written (between August 25th and 26th), the data had to be updated twice, as two new massacres were confirmed… According to Indepaz, up until now 188 people have been murdered in 47 massacres committed so far in 2020. The historical virus of violence in Colombian society has re-awakened and seems unleashed.

According also to Indepaz, most of the massacres occurred in places where the Colombian Ombudsman office had issued Early Alerts on the risks for the local population. Additionally, many of the massacres have occurred in municipalities where the communities massively voted in favour of the Peace Agreement, when it was taken to a popular poll before it was finally signed.

More than 180 people have been killed in massacres during 2020, and as this story is being written (between August 25th and 26th), the data had to be updated twice, as two new massacres were confirmed…

The official reactions to the exacerbation of violence: same old story

The ugly head of an escalating violence comes at a political turbulent time, some weeks after the Colombia’s Supreme Court ordered the detention of former president and right-wing leader Alvaro Uribe, amid an investigation into whether he committed acts of fraud, bribery and witness tampering. Widely viewed as the most powerful Colombian politician of the last two decades, Mr. Uribe had been the subject of investigation for years (including some cases related to alleged collaborations with paramilitary groups), but this is the closest he has come to facing a panel of judges.

As for the Colombian government (which is from Uribe’s party), president Iván Duque has stepped up in defence of his patron and attacked the Supreme Court. And pertaining the massacres and uncontrolled violence throughout the country, one of his initial reactions was very unfortunate:

Mr. Duque decided to appeal again to a rearview mirror, comparing an eight-year period (of his predecessor) with a two-year period (already half of his presidential period), instead of -at least- sending a message of condolences and solidarity to the victims’ relatives. A symptom that once again evidences the government’s negationism of the existence of an armed conflict and a critical security situation in many regions.

Later on, the government made public its first decisions upon the massacres, justifying the reactivation of fumigation of illegal crops with glyphosate, a chemical that has been used many years in Colombia with very low results and high levels of damages to peasants and legal crops; with this decision the Colombian government is undermining even more the efforts of many communities that have committed to the voluntary eradication of illegal crops, one of the key points of the Peace Agreement. Besides, the critical increase of massacres during the past week happened just some days after a judicial action stopped the forced eradication of illegal crops, a policy that the Colombian government has been implementing through military and police members and against the will of the above mentioned communities, scaling the tension to alarming levels of violence and repression, consequently exposing another ugly head of this virus, producing additional deaths of peasants and protesters.

So it was all about more of the same, that is, military solutions to social problems and challenges: new military and investigation units, more presence of the armed forces in regions where the absence of the State has been historical, and where inhabitants have only seen it through uniforms, weapons and military operations, many times intimidating and putting a pressure on their communities, stigmatized as guerrilla members or collaborators.

So it was all about more of the same, that is, military solutions to social problems and challenges.

No vaccine ahead, but…

The rat race to come up with a Covid-19 vaccine has increasingly become a political issue, as the hope to have it ready in 2020 becomes more and more uncertain. Some experts are already saying that only until 2021 there will be a stable result that can enable returning to the so called “new normality”, whatever it may be.

But in the case of this other virus, historically -genetically, I would painfully dare to say- inserted in Colombian social and political history, the horizon for some kind of “vaccine” is unseen, distant and blurry. Risks for rural, indigenous and afro Colombian communities are increasing, human rights defenders and ex-combatants are more vulnerable, and civil society organisations (national and international) are not being heard -even confronted and attacked verbally and through legal actions- by Colombian authorities.

Nonetheless, hope is the essential nourishment for the diverse sectors in Colombian society, including of course the international community, to keep on struggling and dreaming that the opportunity discerned after 2016 with the Peace Agreement is not yet lost, and that we will be able to find paths towards reconciliation, truth and social justice. Colombians deserve a “new normality”, a just and sustainable peace, locally based and daily enjoyed.

Andra nyheter

The power of people powered Public-Private Partnerships

Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) are often discussed in terms of roads, power plants, housing, and other large infrastructure projects. But as discussed on the People’s Partnership Podcast, PPPs are...

ForumCiv’s social media accounts labelled as “extremist materials” in Belarus

Important message to our Belarusian followers. Any interaction with our content can now lead to legal consequences in Belarus. Please read the information below and take the necessary precautions for...

ForumCiv enters new strategic partnership

ForumCiv is proud to announce a new three-year strategic partnership with Sida, totalling SEK 137 million.