False asepsis. From isolation to (“social”) cleansing

Between the night of Saturday 21 and the dawn of Sunday, March 22, in the La Modelo prison in Bogotá, 23 people deprived of liberty were killed by the Colombian National Penitentiary Institute (INPEC, its acronym in Spanish), 83 more were injured along with 7 officials of that institution. According to the Royal Spanish Academy, a massacre is the killing of people, usually defenceless, caused by an armed attack or similar cause. I continue: this massacre was carried out when a protest went out of control and turned into mutinies and escape attempts by the inmates. Prisoners were demanding better hygiene and health conditions in several prisons, as part of measures to prevent the arrival of COVID 19.

Early on Sunday morning, after these events, the Colombian Minister of Justice reported that there had been a successful operation to "stop a massive escape plan from the La Modelo prison in Bogotá". Some mass media prioritized this headline. Next step, the public server gave more details pointing out that, in criminal actions previously planned by the inmates, there had been an escape attempt and, in those events, the aforementioned people were killed. Conclusion: for the Colombian government the responsibility relies on the victims. Finally, she closes her speech stating that in prisons "there is no such thing as a health emergency."

I pause for a moment here, because it is possible that a health emergency is not only a current situation in prisons, nor is it only because of COVID 19.

Our decomposition is much more structural, as it is ethical, and hidden under the oxymoron of the degradation of asepsis.

Let me explain this with three recent facts:

Fact 1: The reaction facing the massacre that occurred this weekend was one of indifference, which is another form of complicity. For several decades now, the idea that killing or jailing the other different has made a career in Colombian society; be it peasant, poor, street dweller, criminal, immigrant, drug addict, homosexual, lesbian, woman, reincorporated ... it is a way of "cleaning" or punishing all those that a conservative society, such as Colombian society, considers abnormal.

The massacre, the arrest and forced disappearance of people (or the "social cleansing" as it has euphemistically been called), as well as the criminalisation of social protest, the judicialization and the arrest of human rights defenders -in other words, punitive populism- are all the equivalent of washing one’s hands off. On the basis of this idea Colombia has suffered the actions of death squads, of paramilitary groups supported by broad sectors of the economy, of battalions that ordered and still order disappearances and executions of civilians, to create the fiction of emerging victorious from an alleged war.

Fact 2: On Friday, March 20, the peasant leader Marco Rivadeneira, spokesman for the People’s Congress and president of the Peasant Association of Puerto Asís Asocpuertoasis, was assassinated in the Puerto Vega - Teteyé corridor in the municipality of Puerto Asís. Marco had been leading concertation processes since last year, aiming to achieve the productive transformation of this region, in the face of non-compliance by the Government of the Peace Agreement component related to the substitution of illicit crops.

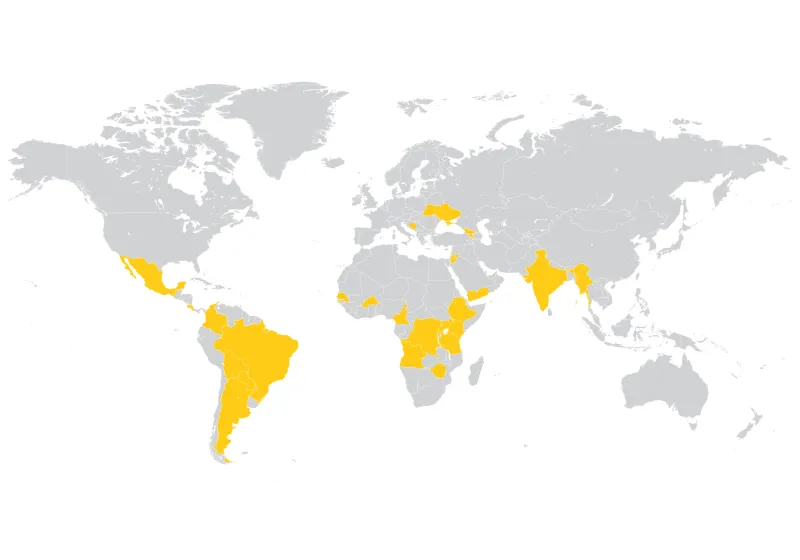

In the same way, Yordan Tovar, a young member of the Putumayo peasant workers union, was assassinated in this same corridor in January. These two publicly recognized murders are the tip of the iceberg of the humanitarian crisis unfolding in the department: pamphlets (see image above) that threaten to "clean up the region" declare that "Venezuelans", "drug addicts", "thieves", and “prostitutes” are military objectives. The mentioned murders have been just two examples of the killings of young people, women and peasants (all of them poor) whose bodies arrive at the morgues in urban areas. The inhabitants of the area report that every week dead bodies appear in the rural areas of Puerto Asís, Puerto Leguizamo and Puerto Guzmán.

Recently, the Inter-Church Commission for Justice and Peace denounced that there is a plan to attempt against the life of peasant leader Jani Silva, president of the Amazon Pearl Peasant Reserve Zone, located in the municipality of Puerto Asís. For more than a year, she had to abandon her farm, leaving her animals, her land and part of her life as a peasant, to go to confine herself in a house in the urban area of Puerto Asís. In that place and already before the COVID19 confinement, she has been living practically locked up to protect her life, that of her children and grandchildren. In the context of systematic assassinations of leaders throughout the country -with a notorious intensity in the Putumayo department-, these new reports demonstrate the eminent risk for Jani’s life.

Also denounced by the Inter-Church Commission for Justice and Peace, these events take place amid the military presence of the Jungle Brigade No. 27, the Police and the Southern Naval Force. According to this human rights organization, behind the wave of death and terror, there is the brother of a renowned drug trafficking boss, who was captured in June 2019 and according to official information, he is linked to an army colonel, who would have been in charge of protecting him.

Fact 3: Between March 16 and 20, the week before Colombia initiated the social isolation decreed as a preventive measure for COVID 19, Irnel Flórez Forero, Belle Ester Carrillo Leal and Albeiro Gallego, reincorporated signatories of the Final Peace Agreement, were assassinated.

191 reincorporated people have already been murdered, and the deaths continue.

Unfortunately, the trend shows that when you read this article, it is highly probable that the number will have increased. Once again, in Colombia a genocide unfolds before the passive gaze of society. These murders are systematic, because they occur repeatedly, methodically and regularly. Since the signing of the Agreement, there has not been a single quarter in which the reincorporated population has not been exposed to lethal attacks; on the contrary, the dynamic remains, following a system, and responding to an organised set of rules.

Given the evidence of these events that at first glance seem unrelated to the pandemic, we must acknowledge how texts on history and literature account for how societies change after these extreme situations. So in the near future, different narratives will tell how this situation affected us in different ways according to social classes; who lost their jobs or who risked their lives on the streets to earn a daily living; how the virus situation affected men, women and sexual diversities differently, for example; how some women had to stay at home looking after their children with their abusive partner.

This humanitarian emergency and the number of deaths that we are adding globally, ends up showing us, as the anthropologist David Harvey states, that 40 years of neoliberalism weakened the social health systems to a degree that, in an era of overproduction and technological developments, due to the will of the states and the big pharmaceutical companies, there is not enough material to face the situation.

Some governments -like the Colombian- will decide to save banks and large private companies, improvise in the sanitary and virus containment measures, deepening the state of emergency, acting criminally and repressively as they did in La Modelo prison, and pretending that indifference extends in this times of isolation. In this way, the privileges of a few can be sustained on the basis of a conservative society that continues to defend openly -and at the same time underhandedly- the idea that societies can be cleansed by killing the different.

Amidst the contradiction, I hang on to the hope of believing that isolation requires us to shift the values of individuality and hyper consumption for those of solidarity, empathy and collective care.

Having time until a few days ago was a rare privilege in this globalised society, so I want - again - to believe that this time can allow us to recognize from otherness, those cultural practices that have justified the idea that some lives deserve to be lived and others do not. By recognizing this system of everyday beliefs and practices, perhaps we can begin to think about how to change those values. This way, “cleanliness” will only be a noun that determines the reality of things and not of social relationships.

Andra nyheter

The power of people powered Public-Private Partnerships

Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) are often discussed in terms of roads, power plants, housing, and other large infrastructure projects. But as discussed on the People’s Partnership Podcast, PPPs are...

ForumCiv’s social media accounts labelled as “extremist materials” in Belarus

Important message to our Belarusian followers. Any interaction with our content can now lead to legal consequences in Belarus. Please read the information below and take the necessary precautions for...

ForumCiv enters new strategic partnership

ForumCiv is proud to announce a new three-year strategic partnership with Sida, totalling SEK 137 million.