Taking care (of ourselves) for gender equality and equity: care as a universal right.

By Daniela Cerón and Valeria Saray **

On June 15th of this year, Promundo launched the State of the World's fathers 2021 report (summary in Spanish, report in English), highlighting the persistence of individual and structural challenges that contribute to the unequal distribution of care work. One of this report's key findings was that 85% of men stated that they would "do whatever it takes to get involved in the early stages of caring for a newborn or adopted child". Despite the increased participation of men, the research reveals that globally we are 92 years away from achieving equality in unpaid care work between men and women.

Furthermore, the research states that the equitable participation of men in providing care benefits men themselves, their partners, their children, and societies. So, how can we transform social representations of care for a fairer and more equal redistribution of care work in homes, society, and the State?

Firstly, recognising that taking care of, be cared for, and self-care is a universal right that strengthens people's agency, taking into account the contexts in which they find themselves. Likewise, the exercise of this right does not depend on sex and the place that the person who exercises and requires it, occupies in society (Pautassi, 2018). Actually, when we talk about care, we refer both to the attention of the needs of dependent people and the needs of those who can self-provide it. This implies attending to our own needs and the logistics required to provide care, the daily organisation of caring for and taking care of oneself, which is usually a mental burden.

Although care has historically been invisible because it is relegated to the private sphere and falls mainly on women´s shoulders (although in different ways and intensities), these tasks have an immeasurable impact on the reproduction and sustainability of life throughout the World. According to Oxfam International (2020), on average, women and girls dedicate 12.5 billion hours a day globally to this type of work, time that represents a contribution to the global economy of at least 10.8 trillion dollars annually. This figure is three times the size of the technology industry. In regions such as Latin America, the average contribution of unpaid care work amounts to 20% of the Gross Domestic Product of each country. These data show the great magnitude of time that is allocated day by day for free in the production of goods and services that provide well-being to society, a huge cost in terms of energy, time, and opportunities for those who perform it.

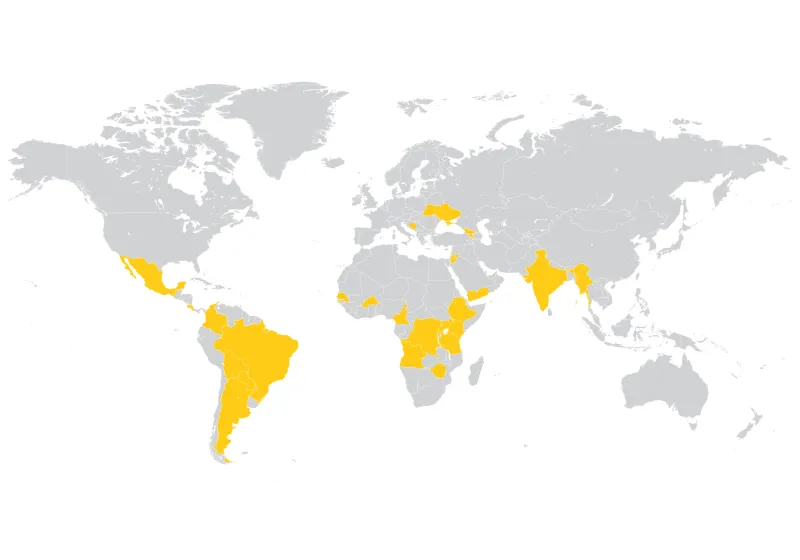

Indeed, there is no country in the world where there exists an equal care provision between men and women. An example of this is the profound gaps in temporality, access, and coverage between maternal and paternal leave. Today, approximately 45% of countries worldwide do not have any paternity policies or leave, denying men the possibility of appropriating care tasks and, thus, reproducing the naturalisation of the feminisation of care. Gender gaps become more visible in the time dedicated to care tasks; women around the world spend approximately three times more hours on unpaid care and domestic work each day than men. This situation was exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic since, as observed in countries like Colombia, the time spent by women in unpaid care work increased significantly, while that of men decreased. (DANE, 2020).

Some feminist postulates sustain that the questioning and transformation of patriarchal gender roles and stereotypes are effective mechanisms for preventing and eliminating Gender-Based Violence (GBV). The opportunity to recognise and appropriate care in its complexity, to strip it of the burdens that the sexual division of labour and gender stereotypes have imposed on it, and to see it as a collective responsibility is a humanising process for men, which allows them to be more in connection with their emotions, to exercise their right to care, to be cared for and self-care, without fear of being judged, which results in an alternative to violence. That is why care, in all its dimensions, is considered an essential element in the fight against GBV.

In this regard, it is necessary to take a series of actions that contribute to transforming the social representations of care that have been established and that have contributed to the maintenance and deepening of gender inequalities. Here are some suggestions: i) recognise international commitments on care (CEDAW, CDN, X Regional Conference of Women in Latin America and the Caribbean, SDG 5 of the 2030 Agenda, etc.) to incorporate standards and principles within the actions of the States; ii) national care campaigns and policies that recognise and redistribute care among household members; iii) provide equal parental and maternal leave with guarantees of social protection, which recognise the right of parents to care for their children throughout their life cycles; iv) recognise and have comprehensive care mechanisms for the elderly; v) transform the social representations of health personnel for the promotion and inclusion of parents as caregivers from the prenatal period, birth and up to the infancy of their sons and daughters; and vi) promote an ethic of care as a human right in families, schools, the media, and government institutions.

The situation previously presented exposes the great importance of care in the reproduction and maintenance of life, its feminisation and unfair distribution in the world. Thus, it is observed the need for care to be recognised as an integral and universal right for all people without any distinction, and not a particular obligation of a specific group - for example, women. This recognition allows all people to have the right to care, receive care and self-care; It also allows us to understand care as a collective responsibility and thus to be able to universalise not only its access but also the burdens, obligations, tasks, and the necessary resources to guarantee it between the State, the market, families, and the community.

Therefore, it is possible to argue that recognising care as a universal right, its redistribution and appropriation of self-care is not only desirable but necessary. This opens the door for the promotion of a greater well-being of all people and of the economic autonomy of women, which translates into a contribution to the development and social growth of countries in terms of human well-being. Care as a right becomes an essential tool in the fight against GBV and, therefore, in the search to establish fairer gender relations. Ultimately, only by taking care (of ourselves) will we achieve the much-desired gender equality and equity.

* ”El cuidado como derecho. Un camino tortuoso, un desafío inmediato” (Our translation)

** ForumCiv's Global Gender Task Group members.

Other recent articles

The power of people powered Public-Private Partnerships

Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) are often discussed in terms of roads, power plants, housing, and other large infrastructure projects. But as discussed on the People’s Partnership Podcast, PPPs are...

ForumCiv’s social media accounts labelled as “extremist materials” in Belarus

Important message to our Belarusian followers. Any interaction with our content can now lead to legal consequences in Belarus. Please read the information below and take the necessary precautions for...

ForumCiv enters new strategic partnership

ForumCiv is proud to announce a new three-year strategic partnership with Sida, totalling SEK 137 million.